WWI — Bloodbaths and Infiltration Tactics

Okay. Let’s go up now to the 19th century. Saw the impact of a lot of modern technology and I want to bring that in.

19th Century Technologies:

Railroad/telegraph

Quick fire artillery

Machine gun

Repeating rifle

Barbed wire

Trenches

Key Tactics

Emphasis toward massed firepower and large armies supported by rail logistics

Increased emphasis on a holding defense

Continued use of frontal assaults by large stereotyped infantry formation (e.g. regiments, battalions), supported by artillery barrages, against regions of strong resistance.

Key Wars:

American Civil War (1861-65)

Austro-Prussian War (1866)

Franco-Prussian War (1870)

Boer War (1899-1902)

Russo-Japanese War (1904-05)

World War I (1914-18)

The point I’m trying to make here is the evolution of tactics did not keep pace with the increase of weapons’ lethality produced by 19th century technology. Saw that in the American Civil War, all the way to culminating in World War I. They’re still going off of Napoleon, Claueswitz and Jomini —large formations, straightforward envelopment tactics — that kind of thing. But you try to do that with all the modern stuff, the result is you get a bloodbath.

World War 1

Let’s start with World War 1, Schleiffen maneuver, 1914. Germans expected a decisive victory in France. The idea is to pivot on Metz, you see these five armies here, get in behind the allied armies and end the war. That’s the basic idea.

What I’m really trying to bring out here, it’s not any more than a huge, what? Single envelopment. In other words, you can think of it as a gigantic flanking operation. You’re trying to swing in a back door, grab the guys, cut them off from their supplies and support, force the surrender and end the war. That was the basic idea behind it.

And the problem there is, ok you’re going after their flank. But you’re doing it on such a wide frontage, and they wanted to do it carefully synchronized so it’s all in a line. You go back and look at it. Christ, it was a goddamn— they were trying to choreograph the thing. If everybody moves together forward, they’re all in line together, how, if the whole line moves forward, how can you get at the other guy’s flank? You’re just going push his line back. You say, we’re going to attack his flank. No, all you do is just push him back and have casualties.

And what happens when you do that, is you go the pace of the slowest unit. Somebody gets slowed up, then you’ve got to tell all the other guys — hey slow it down over there. They did it that way because they felt they needed to protect their own flanks as they advanced. Got to have an even advance so we can protect our flanks.

But it’s not flanks that’s the issue, it’s exposed flanks. In a sense you’ve got to present a flank in order to get at a flank. If I got a tempo or rhythm faster than my adversary, and I’m penetrating, he doesn’t know where the flanks are, you do, you’re carving him up, he can’t carve you up. The issue’s not flanks, exposed flanks are the issue.

And Patton, I mentioned him earlier, he said that — “flanks are something for the enemy to worry about, not me. Before he finds out where my flanks are, I’ll be cutting the bastard’s throat.” That’s Patton himself. He understood it.

Another thing he said, don’t give me crap about holding your position. You’ve heard that one. He was a little more articulate. I think his language is a little more rough1 than what I use here, but the point is, that’s the essence of his message.

Anyway, back to the Schleiffen plan. Then the other problem. What happened? When they run into a strong point of enemy resistance, and what they do is — they throw the reserves in at the point where the difficulty is. Guess what, the defender throws his reserves in there too. What do you got now? A blood bath. Strength against strength. And you just keep piling up strength against strength. You’ve got a blood bath, which is exactly what happened.

And you go back and look, Battle of Verdun, you look at the Passchendaele and all those battles. You see it done over and over again. Both sides. And the defense starts to adapt to this kind of thing. Defense organizes itself into belts of fortified terrain. So-called trench warfare. Two key ingredients, artillery and machine guns, to arrest and pin down the attackers, and eventually the counterattack to throw the bastards out.

You see that gain and again. Example after example, and both sides. The British at the Battle of Somme, they figured, okay. We’re going to break through right here — narrow Somme sector. So they had a one-week artillery preparation, pumped in something like two million rounds of artillery over a one-week period. Just bang, bang, bang.

Well, you know, the other side after a while is going to get wise. Hey, there’s something going on here. Hey guys, we’re coming pretty soon. So that’s a notion of predictability. The Germans saw it coming — took their guys and dispersed them on the field, put them in bunkers, started moving in reserves from other parts of the country. Then the final day of the rolling barrage, the British infantry goes in there with these nice, neat, standard formations. And the British, in the first day the infantry goes in — 60,000 casualties. The first day of a seven-day operation, 60,000. In one day.

Okay. So that didn’t worked. Now what? Battle of Passchendaele — 1917. What’d they do? Let’s try it again. Pumped in four million rounds. They said look, well two million wasn’t enough last time. We’ll double it, all we got to do is we got to double the effort. Didn’t change the plan. They doubled the effort. So they pounded the area. I think they went ten days or something like that. Then they went back in again, standard formations. You ever see those World War pictures, those guys coming out of those trenches all going forward together? They have actual combat films. That’s not just MGM or something. They actually have the combat films. Geez, I wouldn’t want to be in that outfit. That’s an unattractive way to do things. Once again, huge casualties, no appreciable gain. I think like half a million casualties or something on both sides.

So think about that. For a long artillery preparation, what are you doing? Isn’t that just the perfect notion of predictability? Make sure the other guys are ready for it, right? Plus the fact — another notion of predictability — if you’re going to make an assault upon their front, they’re going to know way ahead of time, because in order to dump in those huge amounts of artillery they were pumping into the ground, you’ve got to build up the artillery stockages. And you’re not going to put them 500 miles away. You’ve got to put them near the front, where you’re going to use them. And all that activity’s going on, enemy reconnaissance and intelligence activity is going to build it up. They’ll say hey, they’re getting ready for a big operation here.

What does tell you in the framework of OODA loops? What’s that telling me? You don’t have much initiative, do you? It means you’re not getting inside your adversary’s loop. And he’s not getting inside yours. It’s just sort of a stalemate, going back and forth. You’re not making any progress. You’re just killing one another at a high rate. It’s like an equilibrium condition. Stagnation and equilibrium. Just little gains going each way. And the result is large body counts with no appreciable gain.

So that’s the legacy of Napoleon, Claueswitz, Jomini when you take their ideas into the 19th century. You got these bloodbaths.

German Infiltration Tactics

Okay. What happened? Eventually some people during the war started thinking about that, maybe we ought to find another way to do it. There was initially a French captain by the name of Andre Laffargue, who in 1915 said hey, this is a hopeless way of doing business. He had this idea of small units leaking through the enemy lines. He didn’t have it all right. The French didn’t really pay attention to him. He was their own guy but the French didn’t listen. They said we’ll keep doing it our way. But the Germans captured some of Laffargue’s pamphlets in 1916, translated it, and got right to using it in the war, and they augmented it even more.

Ludendorff, high level general — he saw what they had, he said okay, let’s really train and do this technique, called it infiltration tactics. So while the war was going on, they changed how they were training to do these infiltration tactics. Luddendorff didn’t really understand the nuances — left that to Rohr and Hutier and those guys. And then they used it for the Spring Offensive right near the end of the war, 1918.

This is a map of one of Hutier’s offensives, just an example of their infiltration tactics. But that’s how they did it. Really it’s a four part scheme:

Hurricane bombardment. Intense but brief artillery bombardment, that includes gas and smoke shell, to disrupt/suppress defenses and obscure the assault.

Stosstruppen (stormtroopers) — small squads of thrust troops equipped with light machine-guns, flame-throwers, etc. follow close behind rolling artillery barrage, without any effort to maintain a uniform rate of advance or align formations. Instead, as many tiny, irregular swarms spaced in breadth and echeloned in depth, they seep or flow into any gaps or weaknesses they can find in order to drive deep into adversary rear.

Kampfgruppen (combat groups) — small battle groups consisting of infantry, machine-gunners, mortar teams, artillery observers and field engineers, who follow-up the storm troopers to cave-in exposed flanks and mop-up isolated centers of resistance from flank and rear.

Reserves and stronger follow-on echelons move through newly created breaches to maintain momentum and exploit success, as well as attack flanks and rear to widen penetration and consolidate gains against counter attack.

What do you see here? Something very different since the 19th century. They’re trying to use the Sun Tzu metaphor. Remember what I said last night? Behave like water. Flow through the gaps and crevices, the voids, et cetera. In other words, strength against weakness. Trying to flow through.

And note that they didn’t try to keep their formations nicely lined up. Each one tried to make his own pace through, not worrying about how fast or how slow the guy on the right or left of them are going. Work their way through.

And then the other teams coming in behind them, larger teams, isolating the local centers of resistance, and mopping them up from the flank and the rear. And then the larger units pouring through, these gaps get larger and larger, until you’ve got what Liddell Hart calls a torrent pouring through the front.

Now what I gave you there is a classic description of infiltration tactics, often repeated. Flow like water into the gaps. It gives the reader some nice, vivid images of what this thing looks like. But unfortunately it doesn’t really address how and why the infiltration schemes work. It’s not just about this behave like water stuff — you have to understand the psychological side as well, what you’re doing to the other guy psychologically.

First off, you’re hitting him with fire at all levels. Artillery, mortars, machine guns, army level, division level, various heavy artillery. What you do is you grab the guy’s attention and pin him down. All that stuff going on around him, he’s not going to stand out there in an artillery barrage and all that debris, he’s going to keep his head down. So in other words, you’re clouding his what? His ability to observe what’s going on. And then you’ve got fire, gas, smoke. What you do is you’re cloaking your follow-on movements.

Now the infiltrators, instead of coming through in these nice line-abreast formations, they’re squeezing their way forward, dispersed and irregular character. They’re actually little swarms, little tiny swarms working their way forward. Okay? Permits them to blend against the terrain so they’re also very hard to pick out. Plus all the other crap going on, the smoke, the gas, the fog. They come out of the fog. The defenders, they’ve just got no idea what they’re seeing — just don’t know what the hell’s going on.

And the result is quite simple. The other guy is paralyzed, you pull him apart from the inside — not just physically, but mentally, morally. In fact, I read some reports when these Australians were captured. They said next thing they know— they couldn’t figure out what had happened. All of a sudden, they’re being marched off as prisoners. Game’s over. Being marched off as prisoners, the game’s over. Totally confused. Totally out of it. Never seen anything like this. Note this key word. They were disoriented.

Okay? So what’s the essence here? In a sense you could say all of it boils down to this — cloud and distort your signature. Give that guy as little signature on you as you possibly can have, so he doesn’t know what the hell you’re doing — be indistinct, irregular, hard to understand.

Yet at the same time, you want to operate in such a way as all your swarms have a focused effort going through there. It’s irregular, and dispersed, but it’s focused, where you’re seeking out those weaknesses, the tendons of his system that when severed allow you to penetrate and shatter his organism. Then once he’s paralyzed, you go in and mop up those isolated centers of gravity.

So if you look at it, they’re inverting the concentration principle. All that concentration stuff — that’s what got 60,000 guys killed in a day at Somme. They stopped doing all that concentration stuff, now they’re doing it the reverse — tactical dispersion. Keep all your guys spread apart, irregular — hard to see, hard to hit.

But at the same time, it’s not just all random out there. You’re dispersed, but you have a focus — flow around points of enemy resistance and focus follow-on efforts against weaknesses. You see where you’re having success, and that’s where you focus your efforts. The ones that are hung up, you don’t reinforce those. They just have to sort of hold the position and keep the other guy tied up and reinforce or re-support those guys that are going through and ram that it home through those. And then pump the other guy’s friction and paralyze his effort to bring about his collapse. That’s the idea of the multiple thrusts.

As a matter of fact, the initial plan for Normandy, you only had three thrusts going in there. Montgomery, to his credit, complained like hell. People got mad at Montgomery, but he said, “hey, wait a minute, this is pretty goddamn risky,” he forced them to add two more. They had five going in there. Because what you do is you generate what? More and more ambiguity in the adversary’s mind of what’s going on. You slow down his tempo to respond to that correctly, even on the spot, let alone in the fact that, we’ll talk about later on, the tremendous deception campaign where they locked up a lot of the Germans at Pas-de-Calais area. Very important.

Anyway, you notice what they’re doing — what the Germans are doing here, with these infiltration tactics. It’s a kind of bottom up — start at the tactical level and see what’s working, see where you’re making progress — and then based on what’s working, that shapes your grand tactical and then your strategic.

Compare that to Napoleon. What was he doing? He was doing it as a top-down — start with the overarching strategic plan, and then from there you deduce your grand tactics and tactics. That’s a top-down. These guys do it the other way.

Why were they doing it opposite? They didn’t want to do it that way at first. It was against all that aristocratic tradition, and the obsession with control, and the concentration principal. Why did they go against all that? Simple answer. They had to. They tried it to the other way. They were getting blown apart. This is the way they had to adapt to the lethal aspects of modern firepower. It’s a way they could survive and live and achieve. So they were forced to.

So they turned everything around. Just the opposite. Because they had to.

Okay? So it raised a rather interesting question. They’re inverting all of Napoleon’s stuff, Claueswitz and Jomini too. Going bottom up from tactical to grand tactical to strategic. So you might ask, are these the rejection of Napoleonic methods? You may think so. But maybe they aren’t.

Really in a sense what they’ve done if they’re taking Napoleon’s multi-thrust maneuvers which he conceived of at the strategic level, and bringing them all the way down to the tactical level. In other words, they’re fine-graining those penetration maneuvers all the way — where Napoleon was doing it with a whole army, they’re doing it with a single squad.

Critiquing the Spring Offensive

Of course, in a sense, it still failed. The German’s Spring Offensive — they had initial success, but it ended up stalling out, and they got counterattacked and then lost the war. So why did that happen?

First off, Ludendorff violated his own concept at the strategic level. It worked at the tactical level — they were doing the whole thing, seeking out weakness and sending in their follow-on efforts there. But at the strategic level, Ludendorf kind of reverted back to the previous way — supporting failure not success, sending in reserves on those areas of hardened resistance, rather than focusing on the channels of invasion that were working. In other words, he was going back to strength against strength.

Second, exhaustion of the combat team leading the assault. He didn’t replace the teams as the battle went on, same team at the leading edge the whole time. Later on, like in World War II, the Germans had a reserve, and they would insert the reserve and have a rotation policy for the leading edge units and the other units, so they could keep the operation going.

Third, they didn’t have their logistics together. They didn’t have a supply chain that was flexible enough to get ammunition and reserves to the front. You saw that at the Battle of Lys and also the Aines Offensive — ran out of artillery shells and reinforcements.

Forth, immobile communication lines. And this is a very key one. At the time what they had was telephone lines. They didn’t have the radios we have now. I’m talking about, Christ, they had to string telephone lines. Of course, artillery would be in and cut the telephone lines, and it’s hard to string it. Christ, they were trying to run out the wire all the way up all the time they were charging in.

So that’s going to make it harder. Once it starts, the rear level commander really needs that information flow coming from the front, who’s succeeding and who isn’t. Because depending upon who’s succeeding and who isn’t, that’s how he’s going to allocate the follow-on efforts, so he can go through those gaps. If he doesn’t know who’s succeeding and who isn’t succeeding, he doesn’t know how to allocate people. He’s got to make some kind of an allocation, but it’s not going to be a very bright one.

Fifth, the French use of elastic in-zone defense. Instead of this rigid defense, they have a flexible or a fluid defense. In other words, you pull back from the onslaught. Let your people retreat back, and draw the other guys out beyond their own artillery. Then you dump your guys in behind them, and start choking them off from the flanks and the rear. But you have to have confidence to do that.

The normal way, we say we’re not going to give up an inch of ground. Put our guys in the trench and we’ll take the artillery pounding. Hold the line. Why do you do that to yourself? Well the problem is you’re thinking of terrain as an objective — trying to hold the terrain, rather than seeing terrain as a medium of maneuver that you use to take out the other force.

Remember what I said? Terrain doesn’t fight wars. Machines don’t fight wars. People do it. And they use their minds. In that context, you’ve got to see terrain as a tool, not an objective. I don’t care whether you’re going forwards, backwards, or sidewards or any direction. As long as you have the initiative — you can have the initiative going backwards too, you know. We’re taught if we’re going backwards, we’ve lost initiative. That’s not true. As long as you got him playing your game rather than playing his game, you have initiative.

Because once you take out his force, you own the terrain — whether you’re going forwards, backwards, side wards, or any direction. Then you own it.

Anybody ever read Manstein’s Lost Victories? He was doing the same thing in World War II. Boy, he takes that long step backward, gets the guy strung out, and then cuts his balls off. He gets a whole bag full of prisoners. In other words, he’s using the terrain as a medium for maneuver.

Zeno: There are no lines.

Boyd: That’s right. There are no lines. That’s right. The the only time you have a battle line is before operations start. After that, nobody knows where it is. You’re trying to put all these little lines on the map after the thing’s started. Defending the lines, it’s a hopeless effort. It doesn’t represent anything that’s going on.

WWI Guerilla Tactics

So that was infiltration tactics. Remember what we’re talking about here is how to get beyond the trench warfare. And one of the ways they figured it out was the infiltration tactics we just talked about. But they also figured out another approach, which was different, but it was also similar in a lot of ways. And that was their guerilla warfare.

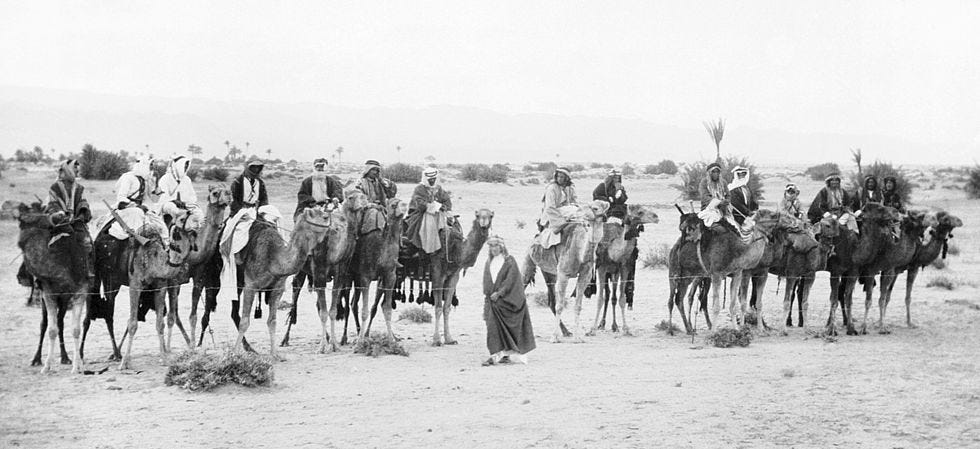

So of course we start with T. E. Lawrence, operating down in Arabia. It was him and a couple of guys on camels. And they took down the Ottoman Empire. He was outnumbered maybe 10:1 at times. And yet he extruded the Turks from Arabia. That was an exact quote there from Lawrence, extruded the Turks from Arabia. Disintegrate the regime, even their ability to govern. How was he able to do that?

Now remember, Lawrence was a scholar. I think he was from Oxford, Cambridge, I can’t remember. He read a lot about this stuff. And he came up with the idea you’ve got to gain support of the population. Very modern notion. Arrange the minds of friend, foe, and neutral alike. Get inside their minds. He recognized it’s mental.

First off, he says combat “should be tip and run, not pushes but strokes, quickest time at the furthest place”. What’s he doing here by doing all this stuff? He’s trying to present a threat everywhere, but yet seem to be nowhere. It’s like the Mongols. That’s the kind of thing they were doing. And so he said, it should be a war of detachment, avoiding contact, presenting a threat everywhere, using mobility, fluidity of action, and environmental background. And that’s what he did.

Remember what Mao said — he said there’s three phases to a guerrilla campaign: the strategic defensive, strategic equilibrium, strategic offense. And in all three phases, it’s tactical offense, tactical offense, tactical offense.

Strategic defense means backing up, but he’s still talking about tactical offense. Strategic defense, tactical offense. What’s he really saying? What he’s saying, it doesn’t make any difference whether you’re going forward or backward. The key thing, do I or do I not have the initiative. And as long as I’m getting the other guy to do the things that I want him to do, rather than what he wants to do, then I have the initiative, makes no difference which direction you’re going in.

So that’s another way of understanding initiative — I get inside my adversary’s OODA loops, I got the initiative. And the reason why OODA loops are important, because it’s human. It’s about people. People have to observe. They have to orient. They have to decide. And they have to act. And if you’re getting inside that, you’re getting inside that guy’s rhythm, his tempo, his natural way of doing business. He can’t play.

And another thing Lawrence says, talks about it in his book. He’s asking himself — how can we be like “an idea, a thing intangible, invulnerable, without front or back, drifting about like a gas?”

And he says, “Armies are like plants, immobile, firm-rooted, nourished through long stems to the head. We might be a vapour, blowing where we listed. Our kingdoms lay in each man's mind; and as we wanted nothing material to live on, so we might offer nothing material to the killing.”

So it’s not just behave like water, Sun Tzu — it’s even more delicate than water. He wants to be a vapour, to be gas. So you’re bringing the idea of fluidity of action, but also the formlessness of a gas. He’s using the terrain as a medium to present some kind of an amorphous image to his adversary, so they can’t come to grips with him, get them unhinged.

So that’s T.E. Lawrence. And before I forget — there was another gentleman by the name of Lettow-Vorbeck down in German East Africa. Anybody read about his exploits down in German East Africa?

In many ways, he was an even better guerrilla fighter than Lawrence because he was totally cut off. The beautiful thing is, he was living off British supplies. Classic guerrilla tactics — living off the other guy’s logistics effort, so to speak. He caused an enormous problem, and he was only a colonel. And he was going up against like 20 or 30 British generals. He made them all look like fools. They always came up with a new plan, they’re going to eradicate him, they liked that word, “eradicate”. And they all fell. They all went down the drain.

As a matter of fact, he surrendered after Germany did during World War I. In fact, he wasn’t going to surrender because he didn’t believe them. The British told him that Germany surrendered. He said, “no, no, you're trying to just get me to give up my force.” It took a lot of convincing. He was stronger at the end than he was at the beginning.

Early on, against the British troops down there. You know what? He won an early battle. Note the word “battle.” He said boy, another one of these victories, I won’t have any force left. He said, I can’t afford those kind of victories. So he got away and started playing the guerilla game — subversion, dispersion very small unit actions. Because he said if I lose my force, I’m out of business.

And what I want to point out here is this stuff that Lettow-Vorbeck and T.E. Lawrence are doing — it’s very similar in some respects to what Ludendorff was doing with the infiltration tactics. In what sense? Very simple. Because they both define the same kind of a game — use clouded/distorted signatures, mobility and cohesion of dispersed units as a basis to pull apart an adversary from within. Same thing in that sense.

And that’s an interesting point. With the advent of modern weapons, rather than the guerrillas gravitating toward the regular force’s techniques, you’re seeing the regular forces gravitating towards the guerilla techniques — because of the lethality of modern weapons. You had to. No choice.

Excerpt from Patton’s speech to the Third Army: “I don't want any messages saying 'I'm holding my position.' We're not holding a goddamned thing. We're advancing constantly and we're not interested in holding anything except the enemy's balls. We're going to hold him by his balls and we're going to kick him in the ass; twist his balls and kick the living shit out of him all the time. Our plan of operation is to advance and keep on advancing. We're going to go through the enemy like shit through a tinhorn.”